British Library Sound Archive - Ju|’hoansi healing songs from the Kalahari

Text by Dr Alice Rudge, Research Fellow at the British Library, and mix by Andrea Zarza Canova, Curator of World and Traditional Music at the British Library. Thanks to recordist Dr Emmanuelle Olivier for her careful research, and for her kind permission for the use of her recordings. We dedicate the programme to the Ju|’hoansi performers who feature in the collection.

The recordings in this selection were made by Dr Emmanuelle Olivier during her PhD fieldwork in the Nyae Nyae area of Namibia in 1993, and during a subsequent trip in 1995. In the style of the French school of ethnomusicology, she created analytical recordings with the aim of documenting the complex interweaving vocal parts that characterise Ju|’hoansi vocal music. To do so, she often used the ‘re-recording’ technique, where singers were played recordings of the group singing through headphones, and asked to sing their part into the microphone alongside the original group recording, allowing for clear recordings of each vocal part to be made.

The recordings Olivier made are now being digitised and catalogued as part of the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage Project, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. Transfer of the Digital Audio Tapes (DAT), on which Olivier recorded, is particularly urgent because these tapes degrade quickly, and the technology on which they can be played is fast becoming obsolete.

The tracks that make up this programme are small selection of the nearly 200 hours of recordings that Olivier made. They were selected for their musical qualities, and to give the listener a sense of the moment in time – as heard through the ears of an ethnomusicologist – that these recordings were made in. We hope that they will provide a starting place for interested listeners to find out more about the music of the Kalahari.

Ju|’hoansi people are a hunting and gathering, and former hunting and gathering people dwelling in both Namibia and Botswana (though Olivier’s recordings were exclusively made with groups in Namibia). They have famously been talked about as an egalitarian society – a society without systematic hierarchy and control of others, including between the genders. The healing dance is the central ritual of their social life, and is one of the many ways in which such egalitarian consensus is upheld. Healing sessions are held a few times a month, and ‘the dance and its beautiful polyphonic music provide a highly social outlet for tensions, a spiritual vehicle for reinforcing the group’s mutual reliance on one another, and a sense of place in their environment. The dance is celebratory, fun, solidifying, and deeply healing all at once… while people with specific sicknesses may be healed, all those participating can experience a sense of joy, renewed social commitment, and spiritual connectedness’ (Katz, Biesele & St Denis 1997:xiii).

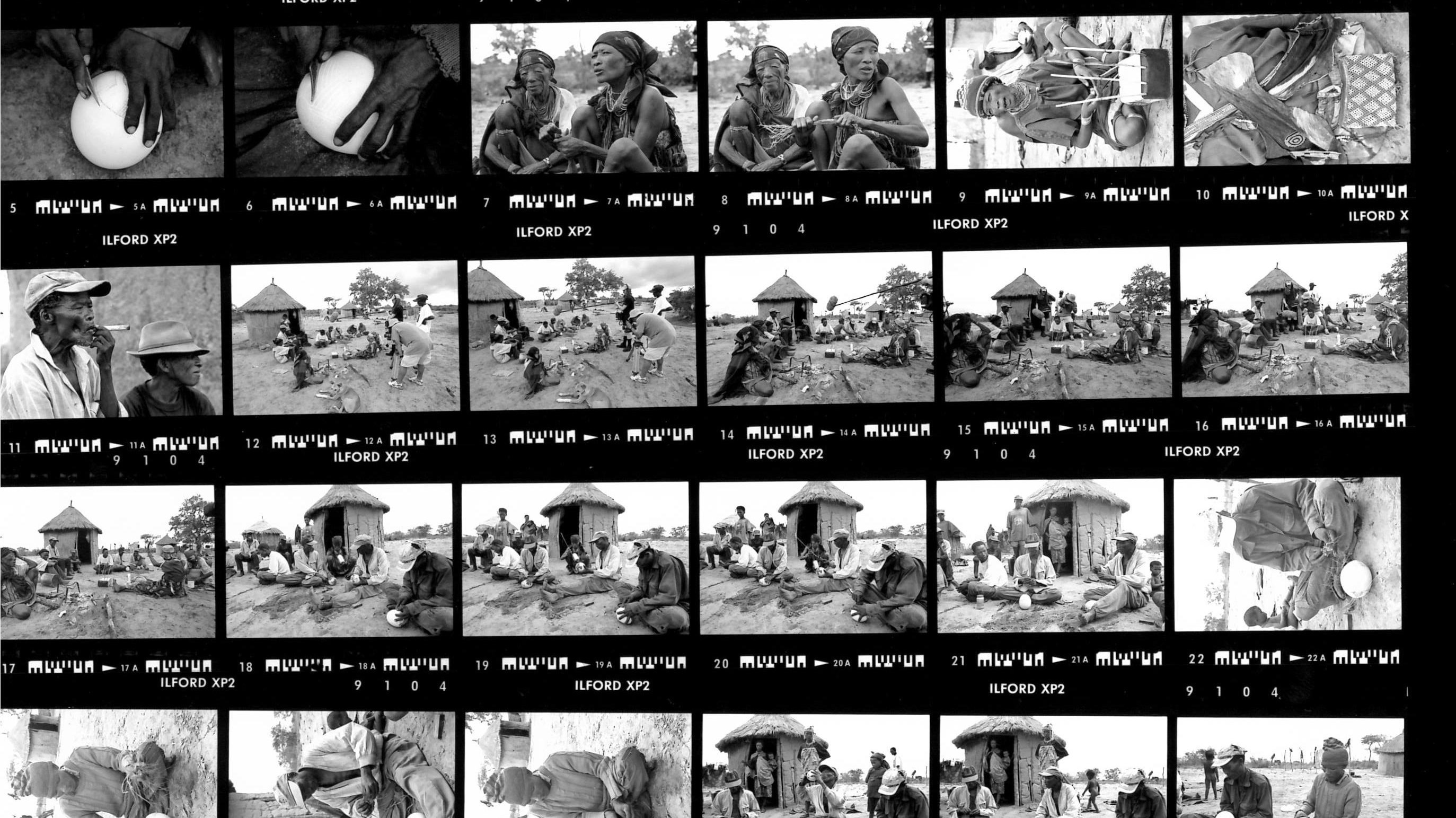

Ju|/hoansi women singing, photo credit to Emmanuelle Olivier

During a healing dance, there is an informal atmosphere. Women begin the singing, and after an hour or two, the men’s dancing then begins to send some people into trance, so that they can then cure others. Many people will be healers, so more than one person may be in trance at the same time.

Healing happens through heating up what the Ju|’hoansi call n|om – a kind of energy which boils when people dance and sing. N|om is said to go from a person’s spine out into their fingers, and then when it is hot enough it allows people to heal by laying their hands on the body and drawing out the sickness.

‘In your backbone you feel a pointed something and it works its way up. The base of your spine is tingling, tingling, tingling, tingling. Then n|om makes your thoughts nothing in your head’

[Kxao ≠Oah - a healer from |Kae|kae area, quoted in Biesele, Katz & St Denis 1997:19]

‘N|um [n|om] is put into the body through the backbone. It boils in my belly and boils up to my head like beer. When the women start singing and I start dancing, at first I feel quite alright. Then, in the middle, the medicine begins to rise from my stomach. After that I see all the people like very small birds, the whole place will be spinning around, and that is why we run around. The trees will be circling also. You feel your blood become very hot, just like blood boiling on a fire, and then you start healing’

[unidentified Ju|’hoan trance dancer, Botswana, quoted in Lee 1993:115]

As these descriptions show - a simple translation of n|om into English is difficult. N|om ‘is not diffuse in the universe, nor is it loose in the air’ (Marshall 1969:351). It is also said to be ‘strong’ – powerful and capable of causing death. Many things can contain n|om – but it has to be activated, or heated up, with singing and dancing. When the n|om is boiling, healers can then go into trance. However, not all music contains n|om – some is just enjoyed for entertainment (England 1995).

Sometimes sicknesses are caused by dead people. A healing song, or a song that contains n|om, might therefore be named for the appearance that the dead person responsible for the illness has taken on – this could be a natural element (such as rain, wind, or water), or a foodstuff (such as honey), or a kind of animal. It could be given the name of the illness that the person is suffering from, or of the patient themselves, or of an animal from which the Ju|’hoansi wish to protect themselves (such as a lion) (Olivier 2001:17). Other songs, such as the men’s initiation tshoma, and the women’s first menstruation ceremony that uses eland songs, are used for these particular social contexts (Olivier 2001:17).

The Nyae Nyae Conservancy, where Olivier made these recordings, has a long and complicated history. The Ju|’hoansi people who call this area home have had to deal with resettlement, apartheid, war, and the loss of a large part of their land (Lee 2003:174).

In 1959, people were tricked into assembling at the town of Tjum!kui (or Tsumkwe) with promises of wage work, agricultural training, and medical care. Instead, they were kept there for two decades by missionaries and the South African authorities, and forced to live on government rations, with no opportunities to hunt and gather bush foods.

Then, in 1978 many Ju|’hoansi people were conscripted into the army to fight in the South African Border War, even though most people were deeply conflicted by their moral view of the war, and their need for work and money. During this time, while the war was in fact still going on, the Department of Nature Conservation within the South West African Administration were pushing to make Nyae Nyae a nature conservation – a game reserve from which all livestock and people were to be excluded. It was planned by the administration that the one exception to this would be ‘a few Ju|’hoansi’, who, ‘for their part, were to dress up in traditional clothes, dance, and sell curios to the wealthy tourists who were to flock in droves to the spectacle’. Understandably, ‘the Ju|’hoansi were appalled by this scheme and opposed it vehemently’ (Lee 2003:176). Finally, after years of protest the scheme was dropped.

In 1989, UN forces entered the area to implement the plan for Namibian independence. A new, independent Nambia emerged in 1990. However, independence for the Ju|’hoansi was a mixed blessing: ‘Namibia faced an uncertain future. For all intents and purposes the new nation was broke, without developed energy sources, its minerals systematically extracted, and its former patron, South Africa, disappearing over the horizon. The hasty retreat was thrown into relief by the hundreds of demobilized Ju|’hoansi soldiers, their livelihood suddenly vanished, lounging around their home communities with a great deal of time on their hands’ (Lee 2003:177). At the same time, neighbouring peoples from other ethnic groups were attempting to take over what remained of Ju|’hoansi grasslands with their cattle.

In the 1980s some Ju|’hoansi people decided that they would try to re-establish themselves on their traditional homelands in the Nyae Nyae area, from which they had been removed decades earlier. The Nyae Nyae Development Foundation helped to provide funds to these groups for them to drill boreholes and purchase cattle, and in 1991 they won land rights over their ancestral areas (Lee 2003:180).

In their fight for land rights, struggles have also been caused by the imposition of foreign democratic modes: ‘the Ju|’hoansi have had to delegate authority and act collectively for the first time, a difficult task for people who prided themselves on their egalitarianism. Through their elected leaders they have had to speak with one voice, not as members of one kin group or band…. A recurrent theme has been how the Ju|’hoansi can meet the challenges of economic and political change without losing their cultural ethos or “soul”’ (Lee 2003:180). The very idea of speaking for another person is anathema in Ju|’hoansi society, which can make decision making difficult in situations where community organising is now necessary. For example, in the 1990s people stressed that each and every person has to be consulted about community decisions ‘otherwise someone might get sick’ (Biesele & Hitchcock 2011:182). The problem of imposing outside models of social structure and decision making on an egalitarian society therefore became evident throughout the 1990s, when this foreign democratic model of community organising ‘actually victimized leaders as well as members, caused elitism problems, and enhanced gender inequities’ (Biesele & Hitchcock 2011:194).

Eventually, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy was formed in 1998. The conservancy is an area where local communities now have the right to make decisions about the use of wildlife resources (Biesele & Hitchcock 2011:199). However, there are still many serious concerns, notably on the environmental impacts of tourism, illegal grazing of livestock by invaders on Ju|’hoansi land, theft of natural resources, and illegal settlement construction. Many of these infringements of the law are simply not being enforced. In the face of these problems, perhaps ‘the most profound lesson offered by the story of the Ju|’hoan people is that as long as there are feelings of dissension, consensus has not been reached and the talk around an issue should therefore not cease. Instead, their view is that community conversation should always be open, with room for second thoughts and slept-upon deliberation to keep it moving in creative ways’ (Biesele & Hitchcock 2011:193)

The recordings made by Olivier therefore present a kind of snapshot – as seen through the eyes of a foreign ethnomusicologist – of a period of great change in Nyae Nyae. They also demonstrate the importance and resilience of a musical tradition that has at its core ideals of empathy and a social commitment to joy, connectedness, and healing.

Track 1 - 00:00:00 [British Library reference number C1709/2 C13]

Giraffe song, 31 October 1993, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This recording was made between 19.30 and 21.00 in the evening. It is a recording of a giraffe song performed by women. The song includes clapping and dancing, and contains the characteristic interweaving vocal parts typical of Ju|’hoansi healing songs. The dance fire was in front of the recordist's tent. Fifteen or so women performed the songs, whilst a man danced in time, wearing rattles on his legs. This track is an excerpt from a longer series of recordings of giraffe songs.

Track 2 - 00:03:34 [British Library reference number C1709/26 C3]

Eland song, 12 May 1995, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

Eland songs are used for the initiation of girls, on the occasion of their first menstruation. Women will dance a slow, deliberate dance, and ‘the entire effect conjures a picture of the grandly muscular, fleshy eland, trotting unhurriedly in the veld’ (England 1995:271). Elands are prized for their delicious, fatty meat. This track is an excerpt from a longer series of recordings of eland songs.

Track 3 - 00:06:03 [British Library reference number C1709/26/7]

Tsamma melon song, 15 May 1995, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This recording was made for a recording session that took place on the 15 of May 1995. It is a medicine song that is named for the tsamma melon Citrullus vulgaris – which is an important water source in the Kalahari. As with all medicine songs, it is sung by women.

Track 4 - 00:08:05 & Track 5 - 00:12:25 [British Library reference number C1709/46 C2]

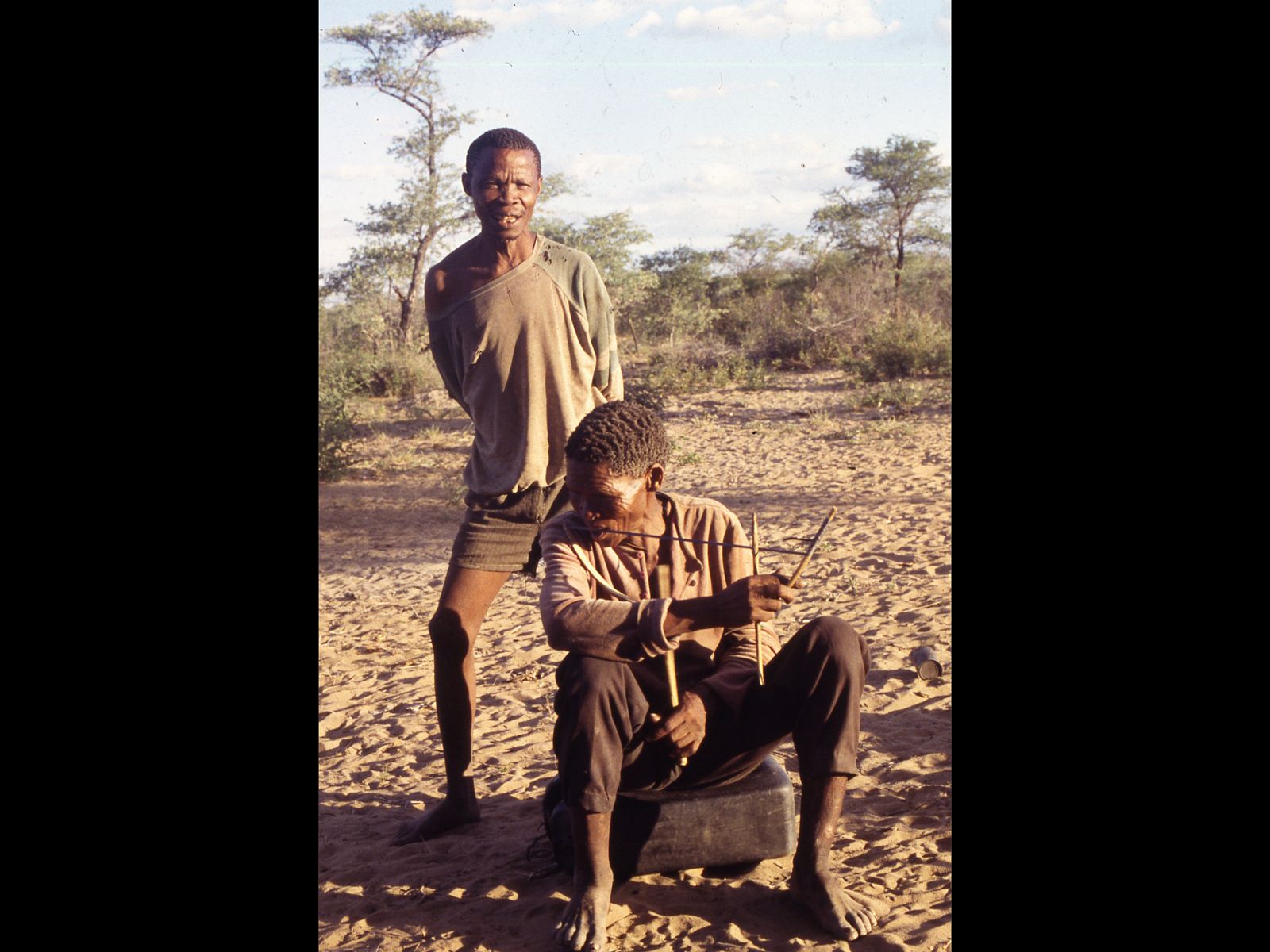

Tshoma, 7 July 1995, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

These are two extracts from recording of a longer tshoma ritual. Tshoma is the boy’s initiation and men’s dance, sung and danced by men and boys only. It is renowned as a very powerful kind of medicine, which can be dangerous for the uninitiated (England 1995:234). Here, the tsin≠a section in track 4 is followed by !’u in track 5 – which signifies the 'bat-eared fox'. The dance is an imitation of this animal, in particular its cries and its gait (Oliver, field notes 1995).

Ju|'hoansi men dancing, photo credit to Emmanuelle Olivier

Track 6 - 00:18:49 [British Library reference number C1709/84 C11]

!Ah bird song, 7 November 1995, ||Auru, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This is a recording of singing done for entertainment with the 5 string pluriarc (a kind of bow lute), or the g≠aukácé in Ju|’hoansi. It is named for the !ah bird (red-crested korhaan, Lophotis ruficrista).

A man plays the 5-string pluriarc, photo credit to Emmanuelle Olivier

Track 7 - 00:22:47 [British Library reference number C1709/6 C2-C1709/7 C1]

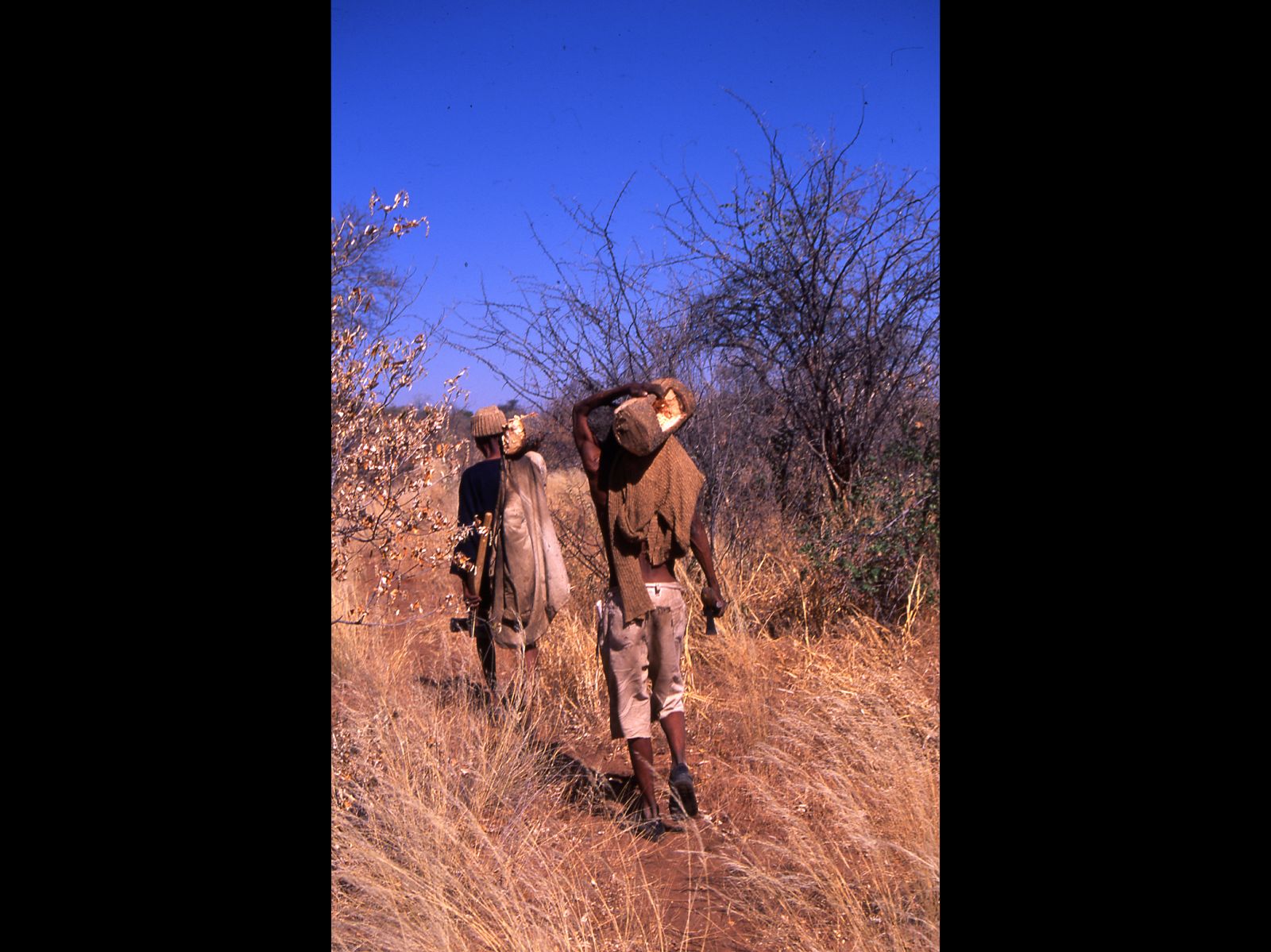

Tshoma, 26 September 1993, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This is a recording of the boy’s initiation and men’s dance, tshoma. The initiation would usually take place after the boy has killed his first few large animals (England 1995:240). This track is an excerpt from a longer recording of a performance of the full ritual.

Men out walking, photo credit Emmanuelle Olivier

Track 8 - 00:31:38 [British Library reference number C1709/5 C7-C1709/6 C1]

Elephant song, 24 of September 1993, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This is an elephant healing song, which took place between 21.45 and 23.45 in the evening. It was performed spontaneously, and – as is characteristic of medicine songs – was sung by women. It is named for a ‘strong’ thing – the elephant. This is an excerpt from the full recording.

Track 9 - 00:36:07 [British Library reference number C1709/84 C6]

G||aru song, 6 November 1995, ||auru village, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

A song played on the dùngò - the lamellophone. This piece is named for the g||xàrú (Lapeirousia bainesii) – a kind of edible plant.

Track 10 - 00:38:47 [British Library reference number C1709/38 C13]

Mamba song, 6 December 1995, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

A recording of a women’s mamba healing song. There was a healer present, whose name is N!ani, who features in many of Olivier’s recordings. He can be heard singing a long introduction before the women join in.

Women sing, dance, and clap, photo credit to Emmanuelle Olivier

Track 11 - 00:42:41 [British Library reference number C1709/83 C6]

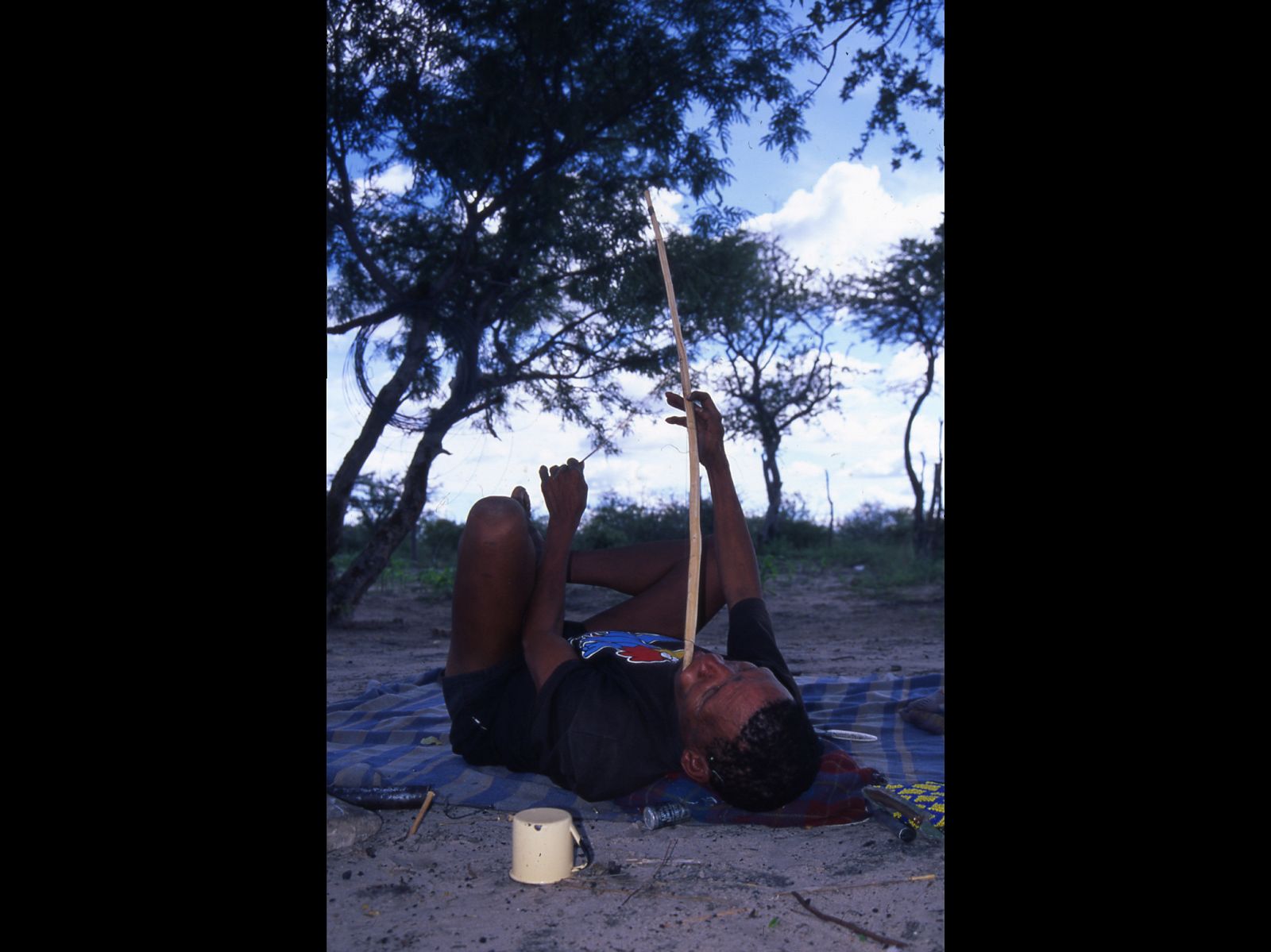

Talk, 4 November 1995, ||Auru, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

An ambient recording of laughter and conversation. The sounds of people playing with the g!omah - musical bow, can be heard in the background.

A man plays the musical bow, photo credit to Emmanuelle Olivier

Track 12 - 00:46:14 [British Library reference number C1709/83 C1]

Well-trodden path song, 4 November 1995, ||Auru, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

A song with musical bow – or g!omah in Ju|’hoansi. The title translates as 'well-trodden path' - the kind on which you can see the traces of the tread of car tyres.

Men play the musical bow, photo credit to Emmanuelle Olivier

Track 13 - 00:51:54 [British Library reference number C1709/15 267]

Lamellophone pieces, 23 October 1993, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

Pieces played on the dùngò, a type of lamellophone. The instrument possesses a body [ámá],a face [|hó], which is part of the table which support the blades, a back [g!òm], which is the hidden face of the table, a head [n|áí], which is the end of the table opposite of the musician, and teeth [tzàùsì], which are the blades, or lamellae. The instrument may be played before hunting, or as entertainment. It is likely that the lamellophone is a more recent borrowing from Bantu-speaking neighbours [Mans & Olivier 2005].

Track 14 - 00:57:52 [British Library reference number C1709/42 C22]

Elephant song, 6 June 1995, ||Xa|oba, Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This final piece is an elephant song, sung by women. You can hear the distinctive ‘panting’ sounds used in some medicine songs.

The collection is currently being digitised and catalogued, and will be made fully available online, as part of the Heritage Lottery funded Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project. It is held under the Library shelfmark C1709.

For more, up to date, information on the Ju|’hoansi, see The Nyae Nyae Development Foundation, the Kalahari Peoples Fund, and Save the San. You can also donate to these groups on their webpages.

Bibliography

Biesele, M., 1993. Women like meat: the folklore and foraging ideology of the Kalahari Ju/’hoan. Bloomington Indiana: Witwatersand University Press.

Biesele, M. & Hitchcock, R. K., 2011. The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Nambibian Independence: Development, Democracy, and Indigenous Voices in Southern Africa. Oxford: Berghan Books.

England, N. M., 1995. Music Among the Ʒũ’/’wã-si and Related Peoples of Namibia, Botswana, and Angola. London: Garland Publishing.

Katz, R., Biesele, M. & St Denis, V., 1997. Healing makes our hearts happy: spirituality and cultural transformation among the Kalahari Ju|’hoansi. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International.

Lee, R., 1993. The Dobe Ju/’hoansi: Third Edition. Toronto: Wadsworth.

Mans, M., & Olivier, E., 2005. Scientific Report for the Project – the Living Musics & Dance of Namibia: Exlporation, Publication & Education. Preparef for the French Department and Cultural Affairs in Namibia.

Marshall, L., 1969. ‘The Medicine Dance of the !Kung Bushmen’. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 39(4): 347-381.

Olivier, E., 2001. ‘Categorizing the Ju|’hoan musical heritage’. African Study Monographs Suppl.27: 11-27.