ALWAYS COMING HOME: A SONIC JOURNEY FROM KESH

Always Coming Home

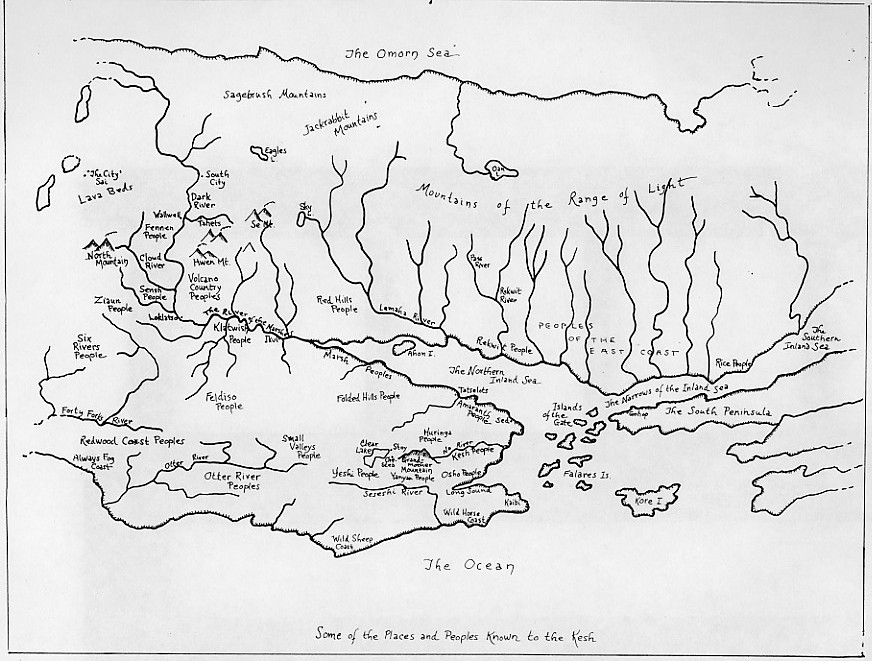

Upon reading Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin, one feels as though entering an anthropological museum filled with artefacts from a past civilization; we can discover maps charting where the Kesh lived, drawings and descriptions of the plants, trees and rivers that surrounded them; collections of recipes and descriptions of how they dressed; detailed notes explaining their society, kinship, sexuality, medicine and funerary rites; folk tales, plays, poems, stories and descriptions of rites and rituals, with detailed descriptions of what their instruments looked and sounded like.

Pandora is the archaeologist, historian and anthropologist who describes the Kesh in this ethnographic account of a non-existent civilization. For both us readers and Pandora, also referred to as the Editor, the Kesh exist in the future, in a post-apocalyptic California. A note at the beginning of the book makes us aware of this with a complex use of verbal tenses—“The people in this book might be going to have lived a long, long time from now in Northern California”. This note is one of the few occasions where we hear Le Guin’s voice, for Always Coming Home is instead a patchwork of Kesh voices that come to life through poems, songs, storytelling, oral histories and a novel, collected or recounted by the narrator Pandora.

Some of the Places and Peoples Known to the Kesh, 1985 © Ursula K. Le Guin. Courtesy of Curtis Brown, Ltd

Always Coming Home was germinated in 1983 when Ursula’s husband Charles took sabbatical from teaching. This enabled the couple to settle for some months at her family ranch “Kishamish”, in the Napa Valley. She had spent the summers of her childhood there, with her brother Karl and parents Alfred Louis and Theodora Kroeber, both anthropologists. As a child, two Native American friends of her father’s, also spent time with the family at “Kishamish”. Exposed to Native American Indian culture from a young age, thanks to her father’s friendship with Juan Dolores, a Papago, and Robert Spott, a Yurok, Ursula was well aware of California’s history and the depth and richness of its autochthonous cultures.

In her creative process for the novel, she created a map for the imaginary valley in which the Kesh lived —“First you dream, then you map the dream”. She played around with the idea of it being similar to Telluride (a county in Colorado) but in South America, high up in the Andes, until it finally dawned upon her that it was the Napa valley of “Kishamish” where the story needed to take place.

Though Native American literature is an inspiration for Always Coming Home, Le Guin was conscious of the moral implications of using real people’s stories, especially when these have been forcefully written out of Western history. The silence around Native American histories, the inaccessibility of their songs and words, the fact that she was “much better at making things up than at remembering them” influenced the creation and development of Kesh civilization in this fictional ethnography of her native yet future Northern California. The novel’s title reveals how in this simultaneous act of getting close whilst distancing herself, Le Guin was able to metaphorically “come home”.

She got to know the landscape of the Napa valley as if it were a character, learning all the names of its plants and trees but also by listening to it, in a present and active engagement with her environment. She listened to the voices of those who had been violently silenced—Native American Indians such as the Wappo, Yurok or Tolowa—not to imitate or exploit them but to gain validation and strength from them, in her pursuit to discover and map the culture of the Kesh.

I finally realized that if I was ever going to find any words in which I could tell stories about my world, if I was ever going to approach the center of the world in my writing, I was going to have to take lessons from the people who lived there, who had always lived there, the people who were the land—the old ones, the first ones, trees, rocks, animals, human people. I was going to have to be very quiet, and learn to listen to them. (Le Guin, 1988/2019: 751)

First release of Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Courtesy of Freedom to Spend

Always Coming Home, was published in 1985 with an accompanying cassette tape on which we can hear the music, poetry and soundscapes of the Kesh. Le Guin asked her friend and composer Todd Barton to help turn her musical intuitions into compositions—“I began wanting to hear the music. I got a real yearning to hear the literature. I could hear the words, but I couldn’t hear the music. So I asked a composer friend, whom I had come to know and respect, ‘Would you write the music for a non-existent people?’”.

Composer and author worked closely together to ensure their Kesh world-view was synchronized before creating their music. In his search for the right instruments with which to record the music, he would bring them to Ursula who would decide if they were “pre-Kesh, or post-Kesh or indeed Kesh”. Barton designed the instruments, and Margaret Chodos-Irvine, the artist who illustrated all the detailed Kesh artefacts in Always Coming Home, drew them. Le Guin felt that by expanding her novel with music and images, she would more readily engage her readers – “The readers, in a sense, have to help me build up the world around them, and, of course, that’s why I wanted the pictures and the music, to give more substance and depth and warmth to this feeling of being inside a different civilization than our own”.

This radio programme takes Ursula K. Le Guin and Todd Barton’s Music and Poetry of the Kesh as a starting point, to trace a sketch-map of its influences. Weaving Native American songs, sounds from the landscapes and wildlife of Northern California and Kesh songs and poetry, it presents the listener with an idea of what life in the Valley of Na might have been like. This is why it is also slow paced and filled with moments of quietude, for Kesh life was slower than ours. Hopefully it’s also an incentive to pick up a copy of Always Coming Home and delve into the fascinating world of the Kesh. Lastly, this programme is dedicated to the memory of Ursula K. Le Guin on the anniversary of her passing, wishing she will always be coming home; moving in the sacred land that is also the commonplace world; dancing the way they dance in the Valley.

Ursula K. Le Guin at her desk in Portland, Oregon, 1972. Courtesy of The Oregonian

Unnamed Performers. “Papago: Girl’s Initiation Ceremony”. Indian Music of the Southwest. Folkways Records, 1957.

The first track in this programme is a Papago initiation song recorded by Laura Boulton (1899-1980), one of the early recordists of the world’s music.

Ursula’s father was the renowned anthropologist A.L. Kroeber who is best known for his work on Western Native American Indians. He worked extensively with Ishi, the last survivor of the Yana Native American Indian group whose life is collected in the books Ishi in Two Worlds, written by Theodora Kroeber, and Ishi in Three Centuries, co-edited by Karl Kroeber and Clifton Kroeber. In her short essay “Indian Uncles”, Ursula K. Le Guin describes the fact that she never met Ishi and instead describes her relationship with Juan Dolores and Robert Spott, a Papago and Yurok respectively, and how they influenced her world-view.

Ed Herrmann. Russian Rivers Birds. North American Free Improvisers. Garuda Records, 1998.

North Owl is the main character in the novel “Stone Telling”, nested within Always Coming Home and also set in the Valley of Na, where the Kesh live. At the beginning of her story she explains the origin of her name – “In Sinshan babies’ names often come from birds, since they are messengers. In the month before my mother bore me, an owl came every night to the oak trees called Gairga outside the windows of High Porch House, on the north side, and sang the owl’s song there; so my first name was North Owl.”

This track was recorded slightly North of where the Kesh would have lived, on the Russian River in Sonoma County, California.

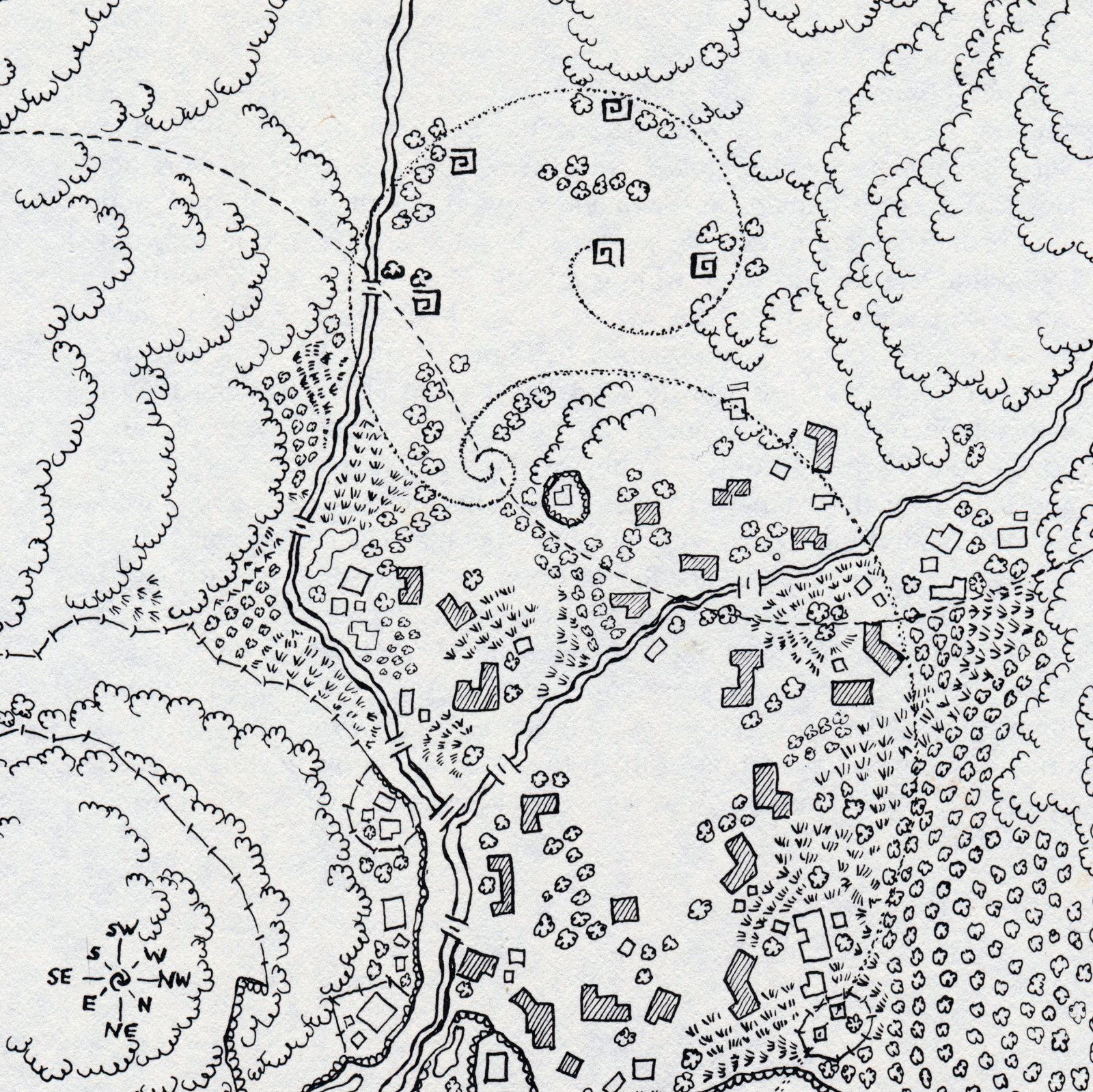

The Town of Sinshan. Drawn by the Editor with the help of Thorn of Sinshan, 1985 © Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton. “A Teaching Poem”. Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Freedom to Spend, 2019.

In this recording we hear Ursula’s voice reading us a poem in Kesh, which according to the liner notes was “Recorded in the Blue Clay heyimas of Kastosha-na.” For the Kesh, the heyimas were the buildings where the activities of the Five Houses of Earth – Obsidian, Blue Clay, Serpentine, Yellow Adobe and Red Adobe – took place. Humans and other beings were divided into these houses, each of which was further associated with specific arts and societies. The Second House of Earth, Blue Clay, is associated with Water Art, such as wells, aquifers, irrigation, sewage and storage.

J. Y. Bosseur et le Collectif Musique Verte. « La boucle du bambou ». Musiques Vertes. Atelier 82, 1982.

“Every Kesh child knew how to make a flute, and there seemed to be endless kinds of flute in the Valley, endblown and sideblown, with or without reeds, made of wood, metal, bone, and soapstone. […] By applying subtle pressure to the reed-holder the player could create stunning microtonal glides, and by sliding the fingers on and off the five holes could produce strange, piercing, wailing, birdlike tones.” (Attebery & Le Guin, 2019: 522)

Loren Bommelyn, Walter Richards, Sr., Sam Lopez (leaders). “Tolowa – Ceremonial Dance”. Songs of Love, Luck, Animals & Magic (Music of the Yurok and Tolowa Indians). New World Records, 1977.

This ceremonial dance is from the Tolowa thanksgiving or world-renewal ceremony and has a striking resemblance with descriptions of Kesh rituals such as The World Dance. It lasts ten nights and is performed at the end of summer or beginning of fall. It should be performed at Yontocket, the Center of the Earth. This is what Bommelyn and Steinruck have to say about the Ceremonial Dance, taken from the liner notes of the release:

The dancers are in a half-circle, the fire is in the middle, and the spectators sit on the opposite side of the pit, completing the circle. Because the circle’s so very important, and the doorway of a house in the old days was round, and this represents the womb of the mother. And each night when you go to sleep, you die in a sense. That day that you have lived is in the past. And when you crawl through that door in the morning, which is always towards the east, you are reborn into that day. So that’s why a circle is really important.

Elinor Armer, Ursula K. Le Guin. “Sailing Among the Pheromones”. Uses of Music in the Uttermost Parts. Koch International, 1995.

Elinor Armer, Ursula K. Le Guin. “On the Antioriental Shores”. Uses of Music in the Uttermost Parts. Koch International, 1995.

In 1985 in Ursula’s home in the Napa Valley, Elinor Armer and Ursula K. Le Guin dreamt up an archipelago of islands – the Islands of the Uttermost Parts – where music was used for purposes beyond listening and was even more essential than it is in our world. Le Guin wrote the words describing each island and Elinor scored them; both drew maps and spoke the poems. The musical excerpt used in the programme describes the island The Pheromones, where “music is sex (scored only)” and we can hear Ursula describe the island The Antioriental Shores, where “music is shadow (spoken only)”.

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton. “Heron Dance”. Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Freedom to Spend, 2019.

“This recording was made at a performance in the only true theatre in the Valley, in Wakwaha. The instrument playing the continuous, slowly varied tone characteristic of Kesh dramatic music (called the Beginning, Continuing, and Ending Tones) is the great horn or houmbúta. Other instruments heard are the bone reed flute, the dulcimer, and the drum, played by professional musicians of the Theater.”

Kesh Mythcon,1988 © Brian Attebery

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton. “Twilight Song”. Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Freedom to Spend, 2019.

Crickets and Coyote, recorded by Lang Elliott, Wil Hershberger, Tod Mack. Insect Concertos. Music of Nature, 2007.

Libation Dorée, The Monastery Of Gyütö. Tibet: Voice of the Tantra. Ocora, 2001.

While from a completely different culture and part of the world, the ritual recorded here sounds similar to many of those described in Always Coming Home. In an email exchange, Todd Barton stated that in the composition of the Kesh’s music, his influences came from many folk and ethnic traditions such as “Javanese, Tibetan, Croatian, Minimalism, and especially the musics of the Tolowa and Yurok tribes of Northern California and South East Oregon”.

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton. “Long Singing”. Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Freedom to Spend, 2019.

“This excerpt from a ‘long singing’ of the Sun Ceremonies of midwinter was recorded in the Obsidian heyimas of Telína’na. The large central room of the heyimas, underground, wooden walled and with a high wooden roof, gives the voices a reverberant quality. About thirty-six people took part in the long singing. Some of them had been singing for about four hours when this recording was made, at midnight, and went on singing until dawn. The syllables sung are those of the word ‘heya’.” (from release liner notes)

Heya is a word crucial to the Kesh – “Heya is not translated in the Kesh glossary at The Back of the Book, but heyiya means sacred, holy, to change, to become, and to praise. The Kesh use heya as a greeting and also as a way to call the listener’s attention to a change of register: from the secular to the sacred, from speech to chant, and so on. This is Le Guin’s tribute to Native American tradition, in which the syllables ‘he-ya’ are common vocables, or wordless syllables.”

Felix Blume. “California”. A Los Cuatro Vientos. Sonic Terrain, 2014.

Big Fields Villagers. “Song of the Green Rainbow (Papago-O’odham)”. Les Indiens D’Amérique. Authentic Recordings. Frémeaux & Associés, 2014.

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton. “A River Song”. Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Freedom to Spend, 2019.

Yurok Brush Dance, Hector Simms (leader). Songs of Love, Luck, Animals & Magic (Music of the Yurok and Tolowa Indians). New World Records, 1977.

“The Brush Dance brings people together in a ceremony to cure a sick child. The medicine woman makes medicine to uplift the spirit of the child so that it will live a good life. About thirty-five men and unmarried women dance in a counter clockwise circle, with the medicine woman and the child sitting in the center facing east. The dancing lasts from dark until dawn for two or three nights, depending on the area. The singers perform both heavy and light [like the one featured here] songs. The heavy songs, which must be sung first, are more religious (heavy with prayer) than the light songs. The heavy, slower songs bring in the spirit, after which the medicine woman prays and all the people focus their attention on her and the child. If everyone is there for the right reasons and has the right thoughts, it brings good to the child.” (from release liner notes)

Desert – Desert Scrub, California Library of Natural Sounds, Paul Matzner. Quiet Places. A Sound Walk Across Natural California. Oakland Museum, 1992.

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton. “Lullaby – Lahela”. Music and Poetry of the Kesh. Freedom to Spend, 2019.

Further Reading:

Always Coming Home: Authors Expanded Edition

Ursula K. Le Guin, ed. Brian Attebery

“Interview with Ursula Le Guin”

Michael Brayndick, Iowa Journal of Literary Studies

Music and Poetry of the Kesh: Liner Notes

Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton, reissued by Freedom To Spend