The Moon Has No Nation: Lunar New Year, Past & Present

Do you ever feel that January 1st doesn’t feel like the start of the year? You’re not alone, for many parts of the world the new year isn’t celebrated until a little while later. Roughly one sixth of the world celebrates “Lunar New Year”, typically around the beginning of Feb though it changes every year according to the lunisolar calendar. The festival has many different names; Chun Jie (春節 or “Spring Festival”) in Chinese, Tết Nguyên Đán ("Festival of the First Morning of the First Day") in Vietnamese, Seollal (설날 or “New Year’s Day”) in Korean.

You might have heard this holiday described as “Chinese New Year”, but it’s celebrated far beyond China, being one of the most important festive celebrations in Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and territories with large populations of the sino-diaspora. Many these days may even find using the term “Chinese New Year” insensitive because it ignores the other cultures that celebrate this holiday - the truth is, it’s a lot more complicated than that.

The festival’s origins have been misattributed as Chinese because the historical period of Chinese dominance saw the imposition of “Sinicization”, i.e the spread of Han Chinese traditions and customs, a process with the goal of assimilating non-Chinese groups into Chinese culture. However, as a wise friend once said, the moon has no nation. The origins of the festival have a history that predates borders and nations, a deeper history as an agricultural festival celebrating the arrival of spring. Instead, it is likely that the invention and spread of the Chinese lunisolar calendar simply standardised the timing of these celebrations for some cultures.

There are actually many “Lunar” New Years celebrated across East and Southeast Asia, and even the rest of the world, that do not follow this lunisolar calendar. Even within China, there are many ethnic minorities living there that have their own lunar new year traditions, for example the Uyghur, Tujia and Hmong, with the Hmong New Year being celebrated as early as September, straight after the harvest. Nearby, Mongolians, Tibetans, Thai, Burmese, Lao and Cambodians also celebrate a different Lunar New Year that does not use the lunisolar calendar.

The truth is there are a lot of different cultures across the region that have spread in ways that defy the neat categorisations of countries. People have been moving around for centuries, bringing with them their traditions, culture and their music. The Philippines is home to the world’s oldest Chinatown - Manila Chinatown is around 400 years old. A lot of Chinese traditions were brought to Manila by Chinese migrants, and you can still find them in practice there. My friend and one of my fave DJs Claire Ting Run Run says that her Chinese Filipino family make nian gao (年糕), a “sticky rice cake” they give to friends and family, “so we stick together”.

This movement of people can be traced back even further; records show that the Hakka and Hokkien people have been migrating as early as the 4th Century, spreading with them their traditions that have been influenced by Sinicization. It is said that they brought this festival to many parts of Southeast Asia, introducing it to Taiwan in the 17th Century. The practice of these traditions grew outside of the Sinosphere, following the great wave of Chinese migration after the second world war.

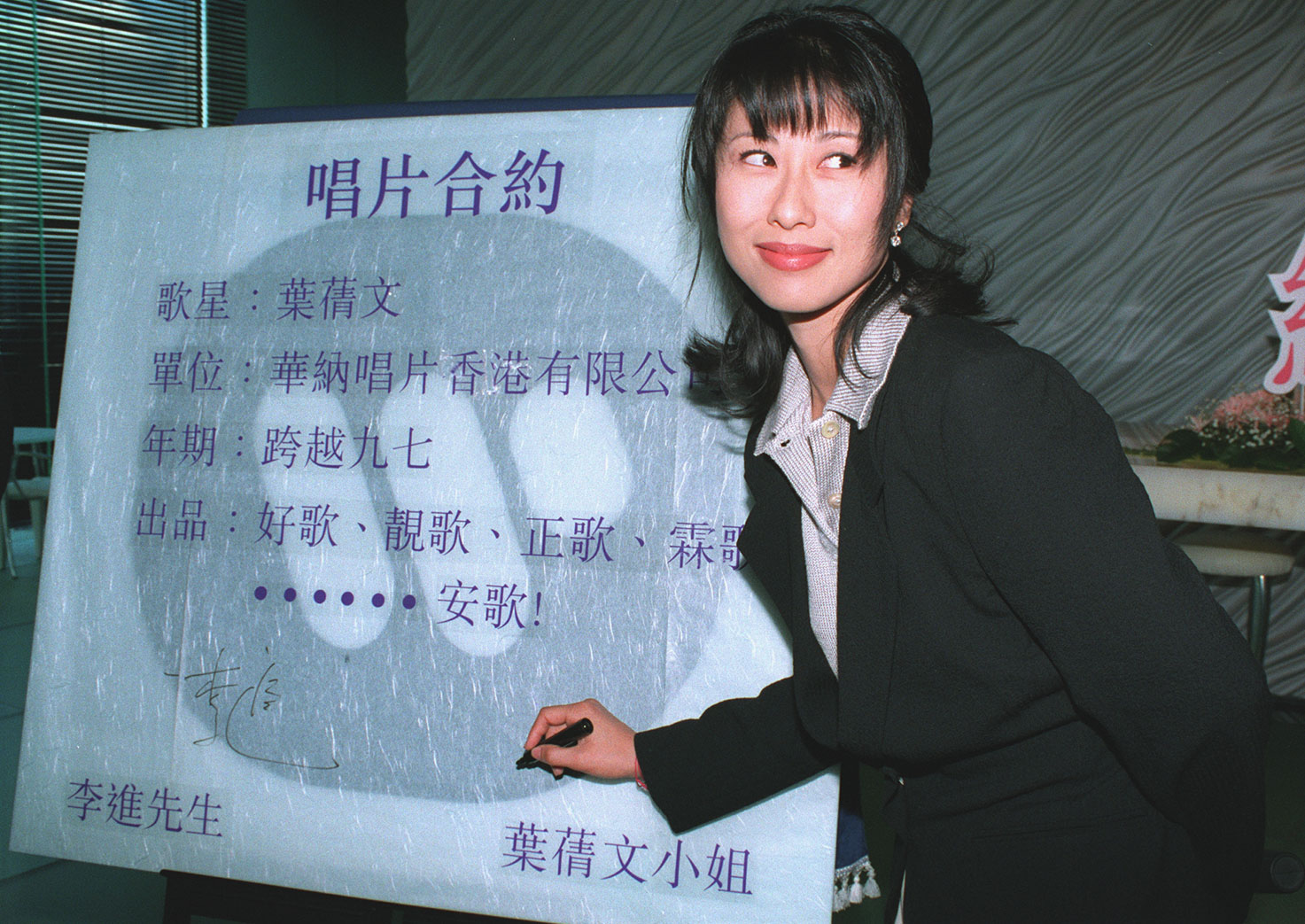

This wave of migration is actually what kept Chinese pop music alive. The 1950s saw mass immigration from China; millions of people left fearing persecution from the Communist Party to make new homes in places like Hong Kong and Taiwan. The People’s Republic of China banned pop-music in 1949, so many musicians were part of this wave of migration. As these new cities became melting pots of culture, the music also evolved, absorbing new influences, but still playing an important role in preserving traditional aspects of their original culture. For example, Canto-pop is one of the ways that the Cantonese language is being kept alive globally. The genre would reach a Golden Age in the 80s and 90s, largely thanks to the expansion of the diaspora, which boosted the genre to become an international phenomenon. You could find people banging Canto-pop tunes across most of Asia, and even in the West.

Culture is messy: you can see how across the region there are a multitude of influences that embed rich chapters of history. There are many shared similar customs and it’s often difficult to pinpoint if they are the result of Chinese influence, other patterns of migration, or indigenous origins. For example, instead of the red envelopes of lucky money you see in China and Vietnam, Korean elders will give their young ones Sebeat Don, pocket money in silk bags made with beautiful traditional designs, along with words of wisdom, and the Vietnamese have their own Zodiac, replacing the Chinese’s Ox, Sheep, and Rabbit with the Buffalo, Goat, and Cat. But, though culture may change over time, it is still important to honour the indigenous roots of Lunar New Year.

Historical records show that Lunar New Year was celebrated long before Sinicization. There are many ancient texts that mention similar festivals in the Vietnamese region; Confucius wrote in the Book of Rites, "I do not know what Tết [Vietnamese for Lunar New Year] is, but I have heard it is the name of a great festival of the Man [old term for “Southern Barbarian”] people, where they dance wildly, drink alcohol, and celebrate during those days." Some traditions may have changed, giant drums may have been swapped for road-side boom boxes blasting Vinahouse (loud-bass fast-tempo EDM) remixes of traditional songs, but a couple thousand years later you will still find people drinking, singing, and dancing wildly to celebrate the arrival of spring.

Similarly, Koreans have also been celebrating this festival for thousands of years. There is early documentation of Seollal (Korean for Lunar New Year) in classical texts Book of Sui and the Old Book of Tang. In fact, when Korea was colonised by the Empire of Japan, they recognised the importance of this festival to Korean culture. As part of their policies that attempted to erase Korean culture and traditions, they banned the festival in 1907. But you couldn’t stop the people from celebrating their traditions. The festival survived, after Korea’s liberation the public put pressure to reinstate the festival, and it became the official Korean New Year and a national holiday in 1989.

Thus, the festival has a deep indigenous importance as an agricultural celebration that predates current formations of nationhood. Like the moon, the culture knows no borders. Understanding the celebration as an agricultural festival makes sense when you realise how a lot of the most important traditions revolve around food - what better way to celebrate nature’s bounty than by eating it? Each culture has their own symbolic foods that must be eaten for good luck, rooted in mythology and folklore. These vary from country to country, and even region to region. For example, Northern Vietnamese eat bánh chưng - square glutinous rice cake with pork and mung beans wrapped in lá dong leaves, said to symbolize the earth, while Southern Vietnamese eat bánh tét, a cylindrical variant made with the same ingredients, said to symbolize the moon. The act of making both is said to represent respect for the ancestors.

Despite all these differences, one thing that unites all these celebrations is the importance of the festive period as a time for families to reunite. Many will cross countries and even continents, sparing no costs to make this journey. In the major cities, it can feel like an exodus since many have left to return to their hometown. I remember one Lunar New Year in Hanoi my grandma rescued some tourists struggling to find anywhere to eat, since everything was closed. She invited them to join our family meal.

Celebrating Lunar New Year far away from home can feel daunting, especially when you feel a pressure to keep up with traditions. What gives me comfort is understanding that this festival has been kept alive for thousands of years by people continuing to practice it no matter how things change. Traditions evolve over time; absorbing different influences from the places they find themselves planted in. Today, the festival has spread all over the world - from Los Angeles, Lagos, to London Chinatown. The diaspora continues to grow even bigger.

Even back at home things change. Robotic drone shows are now just as popular as fireworks. My friends in China tell me you can send red envelopes of lucky money over WeChat now. It’s rare in Vietnam for families to make bánh chưng by hand these days, many order them online. You’re more likely to hear Vinahouse remixes of traditional songs and even ABBA’s “Happy New Year”, the nation’s unofficial Lunar New Year anthem, than traditional versions songs on the streets of Vietnam.